Reliable Data Transfer in Microservices

When you first split a monolith into microservices, you quickly find out data doesn’t like to stay in one place. An order in the Order Service isn’t enough — Inventory has to know, Payments has to know, Notifications has to know. That’s where the headaches start.

At first, it’s tempting to just write the order into the DB and publish an “OrderCreated” event to Kafka in the same request. It feels clean, until the day Kafka is down and your DB commit succeeds. Now the order exists in your system, but no one else knows about it. Or worse: the event makes it to Kafka but the DB rolls back, and you’ve got phantom orders floating in your event log.

I’ve been there. We had ghost events messing up reporting and downstream services quietly missing orders. The fix is obvious in hindsight: never dual-write. But the way you solve it depends on what you care about most.

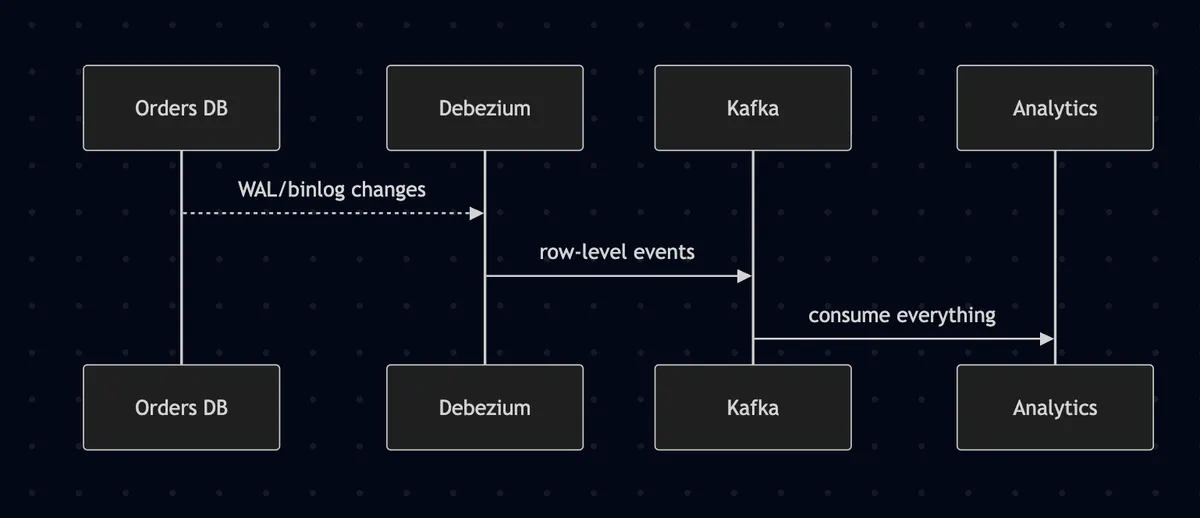

Change Data Capture

The simplest band-aid is to let the database speak for itself. Tools like Debezium tail your transaction log and turn every insert, update, and delete into an event. It’s like flipping on a firehose. You don’t change your app code at all, and suddenly every table change is in Kafka.

CDC is fantastic for analytics, data lakes, cache invalidation, or anywhere you need raw truth. But it doesn’t know business meaning. An update to the orders table might mean the order was confirmed, or it might just mean someone fixed a typo in the shipping address. The consumers have to figure it out.

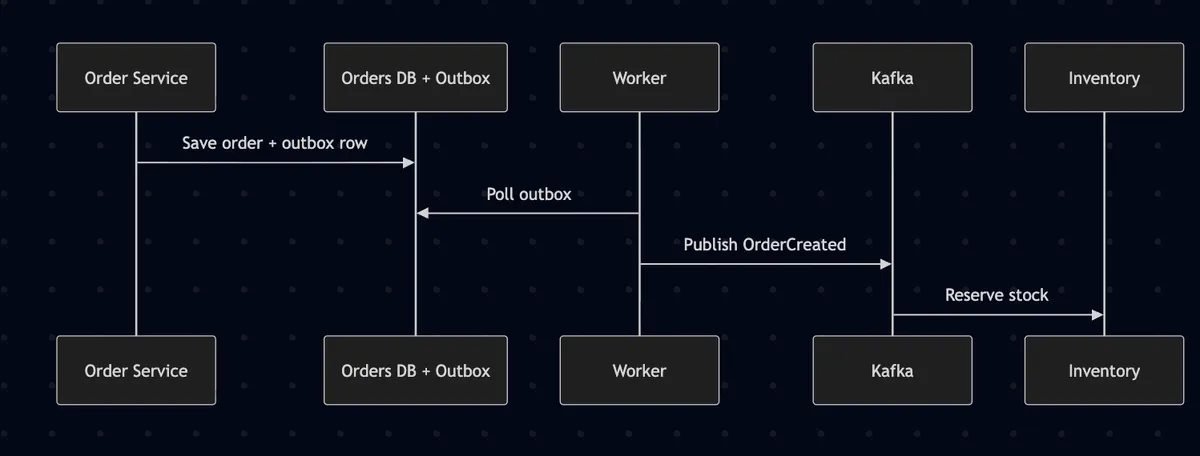

The Outbox Pattern

Sometimes raw row changes aren’t enough. You want business events: “OrderConfirmed,” “CustomerFlagged,” “PaymentCaptured.” That’s where the Outbox comes in.

Instead of relying on CDC to infer meaning from table diffs, you write an event row explicitly whenever you change business data. Place an order → insert into orders and insert into outbox inside the same transaction.

This gives you clean, intentional events with transactional guarantees. If the transaction fails, no event row exists. If it succeeds, the order and event row both exist.

The tradeoff is that every service producing events now needs its own outbox worker — a background process that polls the table, publishes messages, retries failures, and marks rows as processed. That adds up.

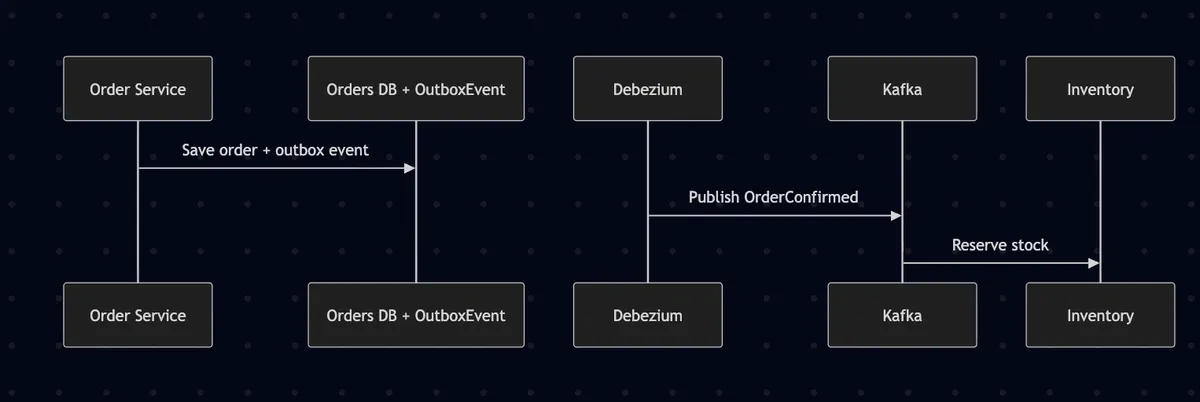

Debezium Outbox

This is where things get interesting. Outbox and Debezium aren’t competitors — they complement each other. Debezium has an “Outbox Event Router” that watches your outbox table and does the publishing for you.

Instead of building polling workers in every service, you just insert rows into outbox_event. Debezium tails that table and turns rows into proper event messages, routed to a topic like Order.OrderConfirmed.

Now you get the best of both: business-level events you designed, but without maintaining worker code across dozens of services.

They Work Better Together

It’s tempting to ask, “So should I use CDC or Outbox?” But that’s the wrong framing. They solve different problems.

- CDC is great for capturing everything that happens to a table — perfect for analytics, auditing, or mirroring into caches.

- Outbox is about publishing the events that matter to other services in your system.

And in practice, you often run both. Use Outbox for clean, intentional business events (OrderCreated, PaymentCaptured) that drive service-to-service workflows. Use CDC to pipe all changes into a data lake, feed search indexes, or keep external systems in sync.

Closing

The real enemy isn’t whether you pick CDC or Outbox. The enemy is dual-writing and hoping for the best. Both patterns exist to stop ghost events and missing updates from creeping into your system.

When you’re early, Outbox feels heavier because you’re adding extra tables and workers. But it pays off in clarity — you know exactly what events exist. CDC feels like magic when you just need the firehose. And Debezium Outbox gives you a nice middle ground: domain events without writing your own publishing code.

If you take away one thing: CDC and Outbox aren’t rivals. They’re gears that mesh together, each turning where the other doesn’t. The trick is knowing when to use which — and not pretending dual-write will ever save you.